A normal day in 2016 felt relatively innocent. There were fewer mergers, fewer redundancies, and far fewer platforms for brands and agencies to capitalise on.

Virtual and augmented reality was the AI, and the biggest crisis facing adland was figuring out how to squeeze Pokémon Go into every possible campaign.

A decade on, a new viral trend has emerged on TikTok and Instagram, with users sharing nostalgic selfies and videos that revisit the era through vibrant filters, throwback songs, outdated fashion trends and familiar memes.

welcome back #2016 pic.twitter.com/vQBppIyr0a

— Tumblr (@tumblr) January 15, 2026

On TikTok alone, the #2016 hashtag has already racked up more than two million posts, capturing an idealised version of life that now feels oddly unattainable, but deeply familiar.

But when it comes to advertising, how much has really changed when viewed through a 2016 filter?

To answer, Mediaweek spoke to creatives, strategists and marketers to unpack what’s changed, what’s improved, and which campaigns from 2016 still hold their place in adland’s collective memory.

What’s changed?

For Sophie Coghill, digital editor at WHO/Are Media, the current nostalgia cycle is less about the year itself and more about what it represents socially.

“The trend isn’t about the year specifically, but instead what the year represents in a social media context,” Coghill said.

“Nostalgia is very much a key factor, and the ‘throwback’ forces audiences to reflect on who they were in 2016 and what the digital landscape was like. And basically, it was much simpler.”

She points to a reversal in how authenticity now operates on platforms.

“Those on social media could be themselves, and content was much more reflective of who users really were in real life. It’s very different to what social media is now, with candid coverage being firmly squashed by curation,” she said.

“Interestingly, in terms of ads, this flips on its head. Ads were highly curated and polished, and audiences could easily distinguish them from the next item in their feed. But now, social media ads centre around authenticity and most come from someone simply sitting crossed-legged on their couch.”

“It turns social media into an advertising arena where we don’t know who the players are and who the spectators are. It’s much more blurry and unclear.”

That blurring has also played out in influencer marketing, according to Lucy Ronald, head of strategy and talent at Fabulate.

“In 2016, influencer marketing was still in its ‘Wild West’ era,” Ronald said.

“Creators like Sharni Grimmond and Michael Finch were emerging as household names, and brands were just starting to realise the power of letting a ‘real person’ tell their story.”

“Back then, influencer marketing was essentially modern-day word of mouth, but scaled through social platforms. Brands weren’t buying polish – they were buying proximity.”

Fast forward to 2026, and Ronald said the biggest shift is expectation, not just technology.

“Audiences are far more media-literate. They understand how content is made, how creators monetise, and how algorithms work. As a result, trust is no longer given automatically – it has to be earned.”

Casey Midgley, founder of Maker Street Studios, said the biggest shift since 2016 has been the industry’s move away from human judgement toward optimisation.

“Looking back from 2026, 2016 reads differently. It was a hinge year,” Midgley said.

“It was the last time advertising still resembled real life. Messy and familiar, but governed by human judgment.”

Midgley said advertising in 2016 still allowed room for instinct and taste, with creative ideas often backed on belief rather than immediate performance metrics.

“You didn’t have to prove its efficiency in the first seventy-two hours or watch it get pulled because a dashboard spiked.”

Midgley pointed to campaigns such as Philips’ Everyday Hero as emblematic of the era, where storytelling was designed to hold attention and reward patience rather than optimise for instant feedback.

“What happened next was speed,” Midgley said. “COVID collapsed the distance between our homes, our politics and our feeds, and as the industry tightened, creative ambition gave way to algorithms and optimisation.”

Has it changed for good?

From an experiential lens, Ben Walker, chief doer at Those That Do, said the change has been necessary.

“In 2016, experiential and activation were often about presence; pop up, brand it, photograph it,” Walker said. “In 2026, they’re about participation.”

“If an activation only works as a backdrop these days, it’s not really an activation, it’s just outdoor advertising glammed up.”

“Yes, it’s changed for the better, because it’s forced experiential to get strategic,” he said. “If it’s not compelling, people won’t stop, and that’s the most honest metric there is.”

For Giles Watson, executive creative director at Clemenger BBDO, the answer is more mixed.

“Sometimes yes. Sometimes absolutely not,” Watson said.

“The upside is faster experimentation, broader access to craft, and platforms that can give ideas the ability to travel further with fewer barriers.”

“The downsides are when efficiency becomes the idea.”

While technology has increased efficiency, Midgley argued the past decade has come at a creative cost.

“The most profound change of the last decade hasn’t been the tools, but the loss of the argument,” Midgley said.

Midgley said the industry’s obsession with removing friction from brand experiences has also stripped friction from the creative process itself.

“That uncomfortable debate is where great ideas are born.” He said

Midgley contrasted today’s work with campaigns such as Doritos’ Ultrasound, describing it as an example of the absurdity and creative risk the industry once embraced.

“By 2026, work passes through prompts and code,” Midgley said. “We’ve traded the soul of the craft for the seamlessness of the machine, and the work is flatter for it.”

Looking ahead, Midgley said the next phase of advertising may require brands to intentionally resist efficiency.

Favourite ads and campaigns from 2016

Coghill points to a campaign that quietly reshaped social advertising norms.

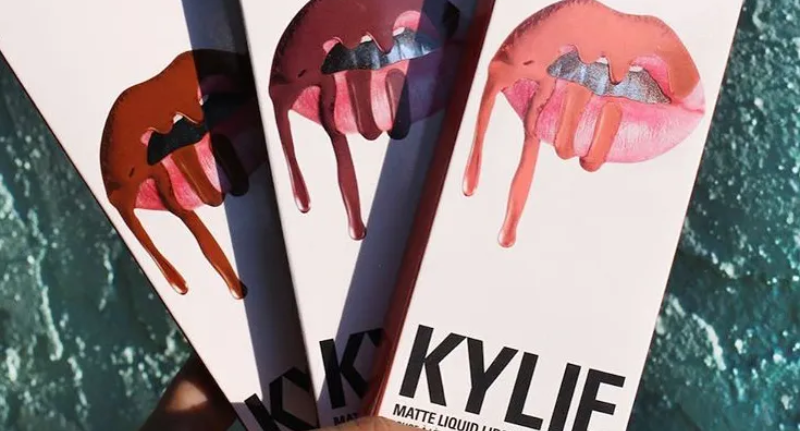

“One social media advertising campaign that stands out from 2016 was Kylie Jenner’s lip kits,” she said.

“Jenner spoke to her audience in a way that only friends had spoken with one another before on social media. This authentic approach is now the gold standard of social media advertising in 2026.”

For Kate Enright, senior copywriter at Think HQ, 2016 remains unmatched in creativity.

“There were ads to set your imagination on fire,” Enright said, pointing to work like The Swedish Number and John Lewis’ Monty the Penguin and the infamous Pokémon Go.

“A creative director I worked with then giddily shared a report that said creative roles were the least likely to be taken by AI. So yeah, times change.”

Yet she remains optimistic.

“That deeply human experience will never lose value, and it’s where our best work lives,” Enright said.

“So, in 2016 style, let’s adopt a useful doctrine of the time: YOLO.”

Walker highlighted Samsung’s experiential work during the Galaxy era in Australia.

“Rather than traditional demos, they created hands-on playgrounds that let people genuinely explore the product through play and discovery,” he said.

Watson’s pick was more understated.

“Looking back on 2016 ads, Doritos Ultrasound sticks in my mind,” he said. “It relied on taste, restraint, and a strong point of view.”

“Tools evolve. Judgment doesn’t.”