The year is 2016.

Yahoo7 journalist Krystal Johnson, who was fresh out of journalism school at the time, was working on a story about Mataio Aleluia, who was charged with the murder of his partner, Brittany Harvie.

The article, headlined “Man paused to take a ‘smoke break’ while bashing girlfriend to death,” included details that the jury had not yet been exposed to.

Johnson’s article drew heavily on a Facebook post by Harvie, which suggested a grim forecast of her fate.

In a section titled “Brittany Harvie predicted her death on Facebook,” Johnson highlighted a chilling message Harvie shared the previous March.

The post included haunting lines like, “It won’t be long and he will put me six feet under. I love him until the day he kills me. He needs a punching bag, we all do,” implying a history of violence in their relationship.

According to the court, Johnson published the piece directly to the website without undergoing the required senior editorial review, violating company policy.

It stayed up online for four days.

As a result, the trial was aborted. A second trial, held a few months later, resulted in Aleluia being found guilty.

Krystal Johnson

Johnson’s employer, Yahoo7 ended up being convicted of contempt of court and slapped with a $300,000 fine.

Johnson, meanwhile, was out on a two-year good behaviour bond, with the Supreme Court of Victoria’s Justice John Dixon condemning the outlet for a “serious lack of proper oversight”.

Back to the classroom

Now, with the Australian public and media captivated by the Erin Patterson mushroom murder trial, it’s more important than ever to understand the boundaries of responsible reporting, and what’s off limits when covering high-profile cases.

Mediaweek spoke with lawyer Nicholas Stewart, who is a partner at Dowson Turco Lawyers, about the issue and he explained why educating the community and media on these matters is so important.

Mediaweek: What is something that media practitioners should not be doing while a big trial is taking place?

Stewart: Don’t jump to conclusions too quickly for the sake of a headline.

Think about the life of a trial – it starts with the prosecution’s case and then falls to the defence to rebut the prosecution.

Have an appreciation for the evidence being considered in the trial.

Running a story based on the contemporary facts coming out of a trial needs to be factual, with no opinion or ‘colour’, because there’s still a defence to come.

Presumption of innocence is key, and while the prosecution may be tendering evidence that seems like the case is open and shut, it’s critical to remain neutral and open to what the defence may put before the Court.

Mediaweek: Could you provide a bit more detail about that? Any examples come to mind?

Stewart: Well, while it’s not relevant to the Patterson trial, I think the media’s reporting has been excellent. However, there have been other trials in which some reporting has fallen foul of contempt committed under the sub judice rule. This occurs when a publication or comment through the media relates to proceedings currently before the court that has the potential to interfere with the proper conduct of the proceedings.

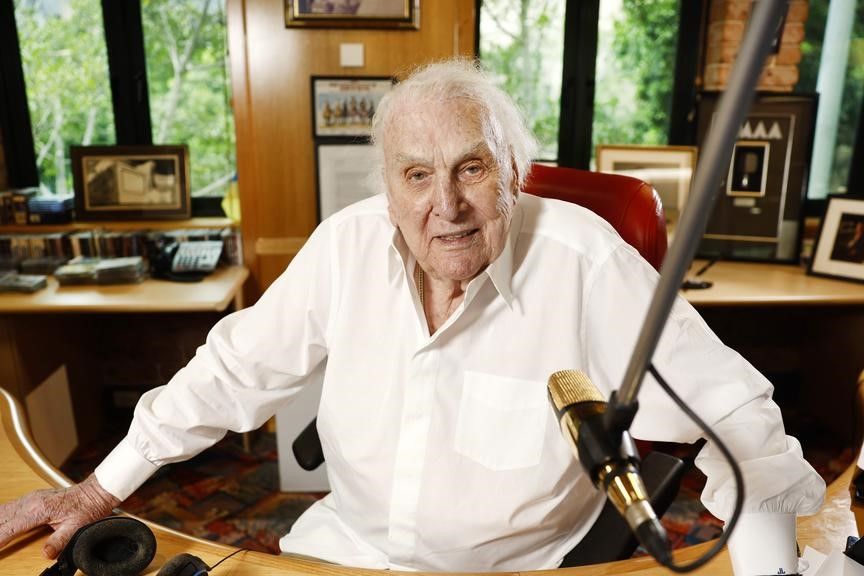

One example was in Attorney General for NSW v Radio 2UE Sydney Pty Ltd (unrep, 11/03/98, NSWCA).

On the third day of a murder trial, John Laws made statements on the radio about the trial. They discussed the evidence while insisting that the accused was guilty of murder and criticising the prosecution’s running of the case. This resulted in the jury being discharged, and John Laws and Radio 2UE were each charged with contempt. They were ordered to pay costs and substantial fines.

The lesson? Stick to the facts, don’t offer unsolicited opinions.

Radio titan John Laws

Mediaweek: What about social media? Can I get charged or fined for a post? Worse still, could a trial be aborted because of a social media post?

Stewart: Social media is great because it democratises the reporting of daily news.

However, at the same time, some social media commentators are entirely unaware of the law of contempt and the risk to the justice system posed by negligent reporting.

Sub judice contempt applies to social media commentators in the same way it applies to journalists and media organisations. They can be charged and fined, too, and I think the risks of social media reporting on criminal proceedings are higher because many social media hosts don’t have media training.

I have seen one particular social media commentator run a regular feed on their own role as a complainant in a criminal matter, even while the matter is the subject of an appeal.

Some of their comments actually risk jeopardising a fair trial of the accused, and, in turn, jeopardising the social media commentator’s access to justice.

Mediaweek: What are your guidelines and tips for posting on social media about a trial?

Stewart: I’d suggest journalists and social media commentators consider the following hypothetical questions:

• Are you neutral, or do you have a conflict of interest to disclose?

• Are there parties to the trial who are protected by anonymity/confidentiality orders?

• Is it appropriate to name or identify a person who has been charged with an offence when the case is in its early stages?

• Are you considering the presumption of innocence when commenting on the proceedings? Have you thought about the defence case? Are you reporting the facts coming out of the trial, or are you speculating on facts that have not come out of the trial?

• Have you considered what might occur if your reporting interferes with the proper running of the proceeding (i.e., is there a chance a juror may see the posts and be influenced by the social media commentary)?

Mediaweek: What about memes?

Stewart: While they are lots of fun, they can be fraught.

Memes are generally great at communicating issues through comedic or satirical graphics.

However, they can still fall foul of sub judice contempt – i.e., have the potential to interfere with the proper running of a proceeding by publishing material that may not be factual or may encourage followers or viewers to come to a premature conclusion about a person’s guilt, credibility, or general evidence.

Sharing a meme that contains content that tends to interfere with the proper running of a proceeding is a form of “publication”, whether that’s on your Instagram Stories, an X post or a Facebook share.

Of course, the number of followers you have is a factor in whether the publication could interfere with proceedings.

Cardinal George Pell and the media scrum during his trial

Mediaweek: Suppose you’re in the court covering the case, or even become privy to some information that can’t become public. Is it legally problematic to discuss the trial details with friends or family members?

Stewart: It’s best to stick to the rule of only speaking about the factual proceedings.

As exciting as it might be to have access to private information, gossip and speculation can spread quickly.

By all means discuss a criminal proceeding with friends or family but stick to what actually happened in court and remind your friends that you can only comment on what you saw or heard in a proceeding, but avoid speaking to matters that the general public is not privy to, to avoid allegations of being in contempt of court.

Mediaweek: What responsibility does the media have in shaping public opinion during an active trial, and how might that influence proceedings or lead to a mistrial?

Stewart: The outcome of the ACT Supreme Court trial of Bruce Lehrmann is a prime example of how the media shape public opinion. Unfortunately, for all parties involved, the trial had to be delayed due to the excessive publicity surrounding it.

Even then, the publicity led a juror to conduct their own investigations, causing the trial to be discontinued and aborted again.

By that time, Brittany Higgins was so distraught that she did not want to participate in a new trial.

The media surrounding George Pell’s prosecution was also prejudicial, meaning it was impossible (in my view) for Cardinal Pell to have a fair trial (although that issue did not feature in his appeal to the High Court, where Cardinal Pell was successful in arguing that there was reasonable doubt about his guilt and that he should not have been convicted).

Mediaweek: How liable is a news outlet for defamatory or prejudicial comments posted by readers on its website or social pages during a live trial?

Stewart: News outlets receive a significant amount of engagement from this type of content, but it poses a substantial risk to both the case and the news outlet or content creator.

I’d suggest that news outlets monitor or even turn off user-generated comments on posts about criminal proceedings (or even prominent civil proceedings) because the use of social media by news outlets means they are controllers of the content that is generated by their posts, and can be held liable in defamation if the comments defame a person.

I’d nevertheless encourage news outlets to share their factual reporting on social media, as it is essential that the public benefits from learning about legal issues in society.

Let’s not forget that criminal trials were one form of prominent entertainment in the days before radio and television were available.

Bruce Lehrmann outside court

Mediaweek: What’s your top legal advice for independent content creators covering these cases without the backing of an in-house legal team?

Stewart: Speak to me! This area is a passion of mine, so I’d love to help independent content creators.

But, the best rule is to think about what is coming out of a trial, who the key players are, and what their evidence is in the witness box?

You can factually report on that while encouraging your audience to think about why the prosecution must prove the elements of the alleged offending beyond reasonable doubt, and reminding them that a person is presumed innocent until they are found guilty. And they may even have grounds to appeal a verdict.