A Gmail-style website called Jmail is turning a sprawling trove of Jeffrey Epstein-related email releases into something you can browse like an ordinary inbox, and it was reportedly built in about five hours.

The project, created by software engineer Riley Walz and Kino AI co-founder Luke Igel, has been updated to include roughly 300GB of newly released material following a late-January document dump tied to the Epstein investigation.

What is Jmail?

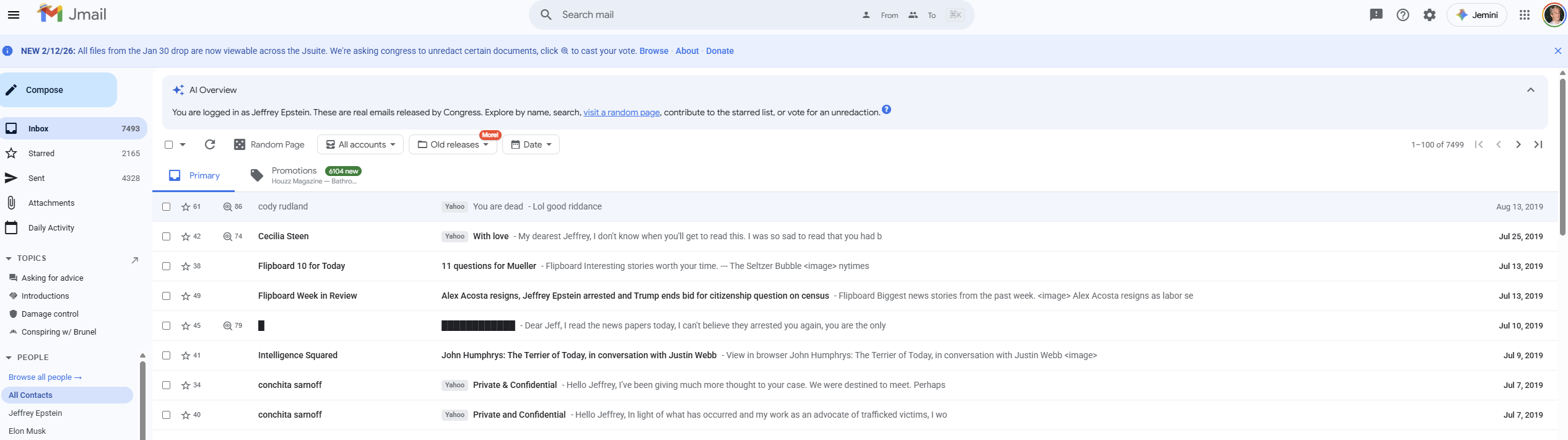

Jmail presents the released “estate emails” in a familiar interface modelled on Gmail, letting users scroll, search keywords, and jump to random entries.

The emails span from April 2009 to July 2019, and include messages with redacted names.

Five hours to build, millions of views later

The speed is the point: and the provocation. In an interview with Rolling Stone, Igel said the team’s build was essentially a two-step process: extract messy email data from PDFs, then rebuild it into a faithful Gmail “parody”.

After launching, the site quickly attracted millions of views, according to Igel.

Why it matters for transparency (and media)

Jmail’s rise puts uncomfortable pressure on an argument that often surfaces around mass public-interest disclosures: that the material is simply too large, too messy, or too technically difficult for meaningful public scrutiny.

Jmail includes an AI search tool (“Jemini”) designed, in part, to counter US Department of Justice assertions that searching through releases is impractical due to “technical limitations”.

Whatever the legal and ethical debates around releasing and redacting documents, the product lesson is clear for publishers, investigators and watchdogs: user experience can be the difference between transparency in theory and transparency in practice.

How users navigate the emails

- Search: keyword search across the archive.

- Randomise: a “dice” icon jumps to a random page of emails.

- Browse: an inbox-style feed that mimics a personal email account.

The bigger question: access versus accountability

For media and communications professionals, Jmail sits at the intersection of access, usability and accountability. It demonstrates how quickly third-party builders can repackage public releases into tools that are easier to interrogate than the original formats.

It also raises an awkward benchmark for agencies and institutions: if independent developers can ship a workable interface in hours, claims of “too hard to search” may face tougher scrutiny: from journalists, lawmakers and the public.