For 15-year-old Noah Jones, the under-16 social media ban only became real when the government acted on it.

That was when he started thinking about how the policy could shape his future online activities.

A month into the ban’s implementation, the outcome has been either shocking or entirely predictable, depending on who you ask.

Tech experts, such as Trevor Long, have already predicted flaws in age-assurance technology and the move toward less-regulated applications.

Noah Jones, who turns 16 in August.

Age verification fails in practice

“It hasn’t impacted me at all,” Jones told Mediaweek. “I haven’t been banned from anything. I did get banned on Instagram. I just made a new account.”

The workaround, he said, was simple. When setting up the new profile, Jones changed his date of birth.

“That was all it took,” he said.

He added that none of his close friends have been meaningfully affected, with most continuing to use the same platforms as before.

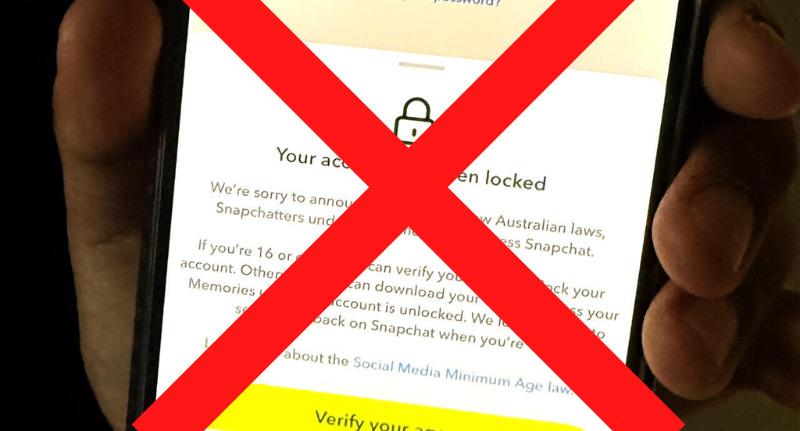

One friend, he noted, was briefly banned on Snapchat, but most have not encountered any lasting restrictions since it came into effect.

Communications Minister Anika Wells said underage access to platforms may be temporary, warning that early workarounds would not necessarily persist.

“Just because they might have avoided it today doesn’t mean they will be able to avoid it in a week’s time or a month’s time,” she said.

The eSafety Commission said platforms that breach the law or fail to take “reasonable steps” to prevent underage users from holding accounts could face penalties of up to $49.5 million.

“If they do offer social media services, they must take reasonable steps to ensure users under 16 do not hold an account,” a spokesperson said.

Despite the ban’s largely symbolic nature so far, the threat of losing access to social platforms motivated Jones to join the Digital Freedom Project, a group challenging the legislation spearheaded by NSW Libertarian MP John Ruddick.

“I felt very strongly aligned with his views, and he asked me to be the plaintiff,” Jones said

While there is broad agreement across the political spectrum that harmful online content can negatively impact mental health, Jones believes the disagreement lies in how the issue should be addressed.

“Everyone knows harmful content exists”

“There’s harmful content on social media, ” Jones said. “We’ve known it for years, and we don’t want to see it either.”

He added that the issue is not exclusive to young people.

Rather than cutting off access altogether, Jones believes the focus should be on dealing with harmful content itself.

Social media as a learning tool

As public debate continues to centre on the risks of social media, Jones said its benefits are being overlooked.

“I learn new things every day from social media,” he said.

From news and politics to major world events, social platforms are Jones’ primary source of information. Without them, he said, he would feel disconnected.

“I wouldn’t know about a lot of what’s going on.”

He argues that social media exposes young people to a range of viewpoints and encourages critical thinking.

“That’s one of the best parts of it,” he said.

For Jones, that’s where the ban falls short.

“I have the right to know those things, and so do other young Australians,” he said.

Economic and creative consequences for young people

Beyond news and communication, Jones said social media also functions as a creative and economic tool for young people.

Many teenagers with entrepreneurial ambitions or creator aspirations may never get started, while others risk losing accounts they have already built.

“There are young creators right now who are losing accounts that could be income or savings for them,” he said.

While Jones does not consider himself an influencer, he believes the ban still disrupts how young people build and share ideas online.

“I don’t think I’ll be an influencer, but I’ll probably use social media for marketing one day,” he said.

With brands increasingly allocating large portions of their budgets to influencer marketing, Jones questions how young people are meant to aspire to start businesses or become creators when access to social platforms is restricted.

“How else would you market anything now?” he said. “If a 14-year-old wants to start a small business, how do they get it out there without social media?”

ByteDance wins

Another major concern, Jones said, is that teens are already shifting to less regulated platforms.

“One of my friends got banned on Snapchat and TikTok and moved to Bluesky and Lemon8,” he said

.

Lemon8 was the most downloaded platform (iOS) on 10th December. The app, a photo and video-sharing platform that closely mirrors TikTok’s format, is owned by the same parent company, ByteDance.